Abkhazia – in the Subtropics of Isolation

The issue of the 90s’ wars is like a Pandora’s box for Georgia. In today’s Georgian context, the history of the Georgian-Abkhazian conflict remains unexplored and unresolved. Unfortunately, this conflict continues to be a heavy burden for people to bear. It is frozen, albeit ongoing.

What is Abkhazia, and where is it?

There are many places on Earth where you can feel that time has stopped. Abkhazia is precisely that place.

Abkhazia is a region in the South Caucasus, internationally recognised as part of Georgia. North and West of the region border the Russian Federation. The East is connected to the Samegrelo-Zemo Svaneti region with the Enguri river serving as a boundary between them. The Black Sea is located to the South. Abkhazia lies in a subtropical climate zone, with sea, fertile soil and mountains. In the Soviet times, Abkhazia was an Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (ASSR) within the Georgian Socialist Soviet Republic (SSR). Caucasian Riviera was how Abkhazia was referred to in the USSR. It was a prosperous, beautiful, wealthy with nature and resources, rich in culture and ethnic composition.

Abkhazians have their own language, customs and traditions, specific for Caucasian people. The language belongs to the Northwest Caucasian language family, together with the Circassian and the Abaza languages. Before the 1992-1993 war, this small region accommodated people of many cultures and ethnicities. With a population of 535,100 people, whereas Georgians were around 244,000 (~46%), and Abkhazians 94,000 (~18%), Abkhazia was also home to Armenians, Greeks, Jews, Ukrainians, Estonians, Russians and others. After the war, the population was reduced. Around 240,000 ethnic Georgians were forcefully displaced to other regions of Georgia.

What happened before the war?

Let’s turn back the clock quickly. In 1977, the USSR adopted a new constitution, according to which Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia had to grant the Russian language the co-official status, which in practice meant that Russia would have taken the ever-dominant position. On April 14, 1978, a massive peaceful demonstration took place on the main streets of Tbilisi, demanding to preserve the status of the Georgian language. Somehow, the leader of the Georgian Communist Party, Eduard Shevardnadze, obtained permission to maintain the previous status of the Georgian language. Since 1990, April 14 has been celebrated as the Georgian language day.

Maintaining the language soothed the situation between Georgians and the Soviet leaders but triggered tensions in Abkhazia. In May 1978, after the events in Tbilisi, a rally occurred in Sokhumi, where the Abkhazian public demanded a provision for the Abkhazian ASSR to change its subordination from the Georgian SSR to the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR). The 1978 Constitution confirmed the autonomous status of the Abkhazian ASSR within the Georgian SSR. Funds were allocated to the economic development of Abkhazia, as well as cultural benefits such as the establishment of the Abkhazian State University, the release of magazines in the Abkhazian language, whereas before it was only in Russian and Georgian, and the creation of an Abkhazian-language broadcast and a State Folk Dance Ensemble in Sokhumi.

Next?

The most important event for Abkhazians and Georgians took place in 1989 in the village of Lykhny where 30,000 ethnic Abkhazians gathered and appealed with a letter to the head of the USSR, Mikhail Gorbachev, demanding the status of a union republic within the USSR be granted and restoring the status of an allied republic that Abkhazia had in 1921. The demand was immediately rejected, but some changes and concessions were made. Specific quotas were established for bureaucratic posts, giving Abkhazians more political power. Georgians living in Abkhazia protested against the discrimination they were subjected to by the elite of the Abkhazia Communist Party and called for equal access to autonomous structures. Slowly, the tension between Abkhazians and Georgians was rising.

9th of April

Every Georgian remembers this day clearly. The events of April 9 were a watershed for the national liberation movement of Georgia.

Georgia declared independence from the USSR on April 9, 1991. The peaceful demonstration, demanding separation from the USSR, was suppressed by the Soviet troops. As a result, 21 people died, and 427 were injured. After achieving independence on December 26, 1991, during most of the following decade, Georgia suffered from two interethnic wars, a civil war in Tbilisi, and total disruption of the state institutions. The involvement of different groups with different interests and ideologies, trying to take control of the state, aggravated the situation. While the statehood of Georgia was barely stable, the Abkhazian people started the secessionist movement. Abkhazians were supported by mercenary groups and volunteers from Russia and some of the North Caucasian republics who were the members of the “Confederation of Mountain Peoples of the Caucasus” organisation, which was established in Sokhumi in August 1989. These groups of people assisted Abkhazians in the war.

On August 14, 1992, the war between Abkhazians and Georgians in Abkhazia started. Russian presence in this war is an integral part of the outcomes and the consequences of the war. September 27, 1993, is considered the end of the military phase of the conflict. The war ended with the defeat of the Georgian armed forces, resulting in considerable casualties, the separation of Abkhazia from Georgia, more than a 240 000 of internally displaced people and a self-proclaimed state – the Republic of Abkhazia.

Observation Time

Each travel to Abkhazia is a new and inimitable experience for me. Last summer, I went home to Gali, the Easternmost town in Abkhazia, inhabited chiefly by Georgians. It was my first travel to Abkhazia, where I wouldn’t spend time only with my family or Georgian friends but with Abkhazians, whom I met on a peace-building project in Belgrade and Istanbul.

I went to Sokhumi, the capital, to enjoy the fantastic views and slow pace of the scenes of the seaside. It was more of an observation of me with the environment rather than travel. I noticed how my attitude changed as I knew I had five friends in the town – I was not alone here.

During this observation, my Georgian friends, internally displaced from Abkhazia, asked me to take photos of their houses in Sokhumi. I could grant only one friend’s wish but not the other two. This time, I found a car wash instead of the house of one of them, and at the other, I found the city prosecutor’s office. Observation continued.

At another peace-building conference in Istanbul, where journalists, psychologists and ex-combatants worked together on the transformation of conflict and rethinking history, I met Batal. There, Batal, 55, stood out from everyone with his empathy and understanding towards the people, from another side of the conflict. We promised each other to meet in Sokhumi whenever I could, and we kept this promise. During our walk in the Maiak district of Sokhumi with his granddaughter, he told me how much he has contributed to Abkhazia, what he remembered from the times before and during the war, where he sees Abkhazia’s future and whether reconciliation is possible.

„I was 16 when the war started. Since that day, I had to become a man, and childhood was over. Frankly, it didn’t surprise my family members; they were also preparing for the war. I always hated the USSR for its‘ values‘, which were empowering one nation whilst neglecting the importance of others. We felt like that throughout the history of the USSR. I feel sorry for the loss of both Abkhazian and Georgian people.“ – said Batal, an ex-combatant awarded the Hero of the Abkhazian War title.

For the next mission, I moved to New Athos, a nearby city on the West of the capital, where I had to meet the sister of my friend from Tbilisi – Neliko. When the war erupted, she was 21 years old, and as an ethnic Georgian, she had to flee with her family. While searching for refuge, she changed her place of stay a couple of times, even lived in Sweden for three years, but eventually came back to her origins, Abkhazia. She was very caring, warm and welcoming and told me mind-blowing stories from the past and present over a cup of sweet coffee. She remembered about her last student years: “I remember I was at the university when I learned that the university lector had also signed this appeal. I was shocked when this happened because I was his Georgian student, among hundreds of others, and I felt threatened by something. He was befriending my Georgian family and a lot of Georgians around, so it would never appear to me that he had something against Georgians.” – says Neliko, who then studied linguistics at the Abkhazian State University. Today she teaches English to students at home.

Since the war until today

Time has slowed down in Abkhazia, almost stopped. Some buildings have stood in the same position since the war’s end, wrapped in dense vegetation that gives them a sense of stillness and tranquillity while life continues. Despite many endeavours of the Abkhazian people to be recognised as an independent state, only Russia, Syria, Nauru, Nicaragua, and Venezuela have recognised it. Not long ago, Taliban authorities travelled to Abkhazia to meet with the Minister of Foreign Affairs, which speaks volumes about the diplomatic preferences of the de-facto Abkhazia government, that for now takes a sharply pro-Russian vector. The more closely Abkhazia maintains relations with Russia and its allies, the more isolated it remains from the outside world, which is like a vicious circle.

Meeting Abkhazians and having candid conversations with them, was a valuable experience for me.

“I always wanted to meet Georgians. Not because I consider you my enemies, I just wanted to make it clear who we are for each other. Truthfully, I’m curious how Georgian youngsters are having fun, how you dress, what kind of music you listen to, how you dance, who you love or hate, do you travel and where, and what you think about us Abkhazians?” – asked a young girl from Sokhumi.

I told her I was thrilled to be there in Sokhumi with my new acquaintances, having humane conversations without a third party involved. I hoped I answered all those questions and satisfied her curiosity.

“This is a safe place for us to gather, share a thought, have a drink, and sometimes meet new people. But most importantly, we gather here to dance and let go of the unpleasant emotions and energies embedded in us since we were children that were brought by the war and isolation. Here it goes away, and this view is just thrilling, right?”

It happened in the pace of the frozen conflict, in a cosy techno club on the eleventh floor of the old sanatorium in Sokhumi, with unbelievably suitable views and music, among Abkhazian youngsters eager to dance and free themselves from social boundaries and outcomes of the war that were just outside of the club. They seemed free, young, beautiful, and enthusiastic about adventures and the fresh breeze of a new friendship. We danced fiercely together as we compensated for every missed chance to dance together before. This meeting and connection happened unexpectedly, making me face very interesting thoughts embedded in my mind a long time ago. They floated up immediately, and I had no choice but to meet and answer them. This meeting and connection with people showed me how similar and different we are. Distinct thoughts were coming to my mind, but the most frequent one was: what if not the war? It all felt surreal and new.

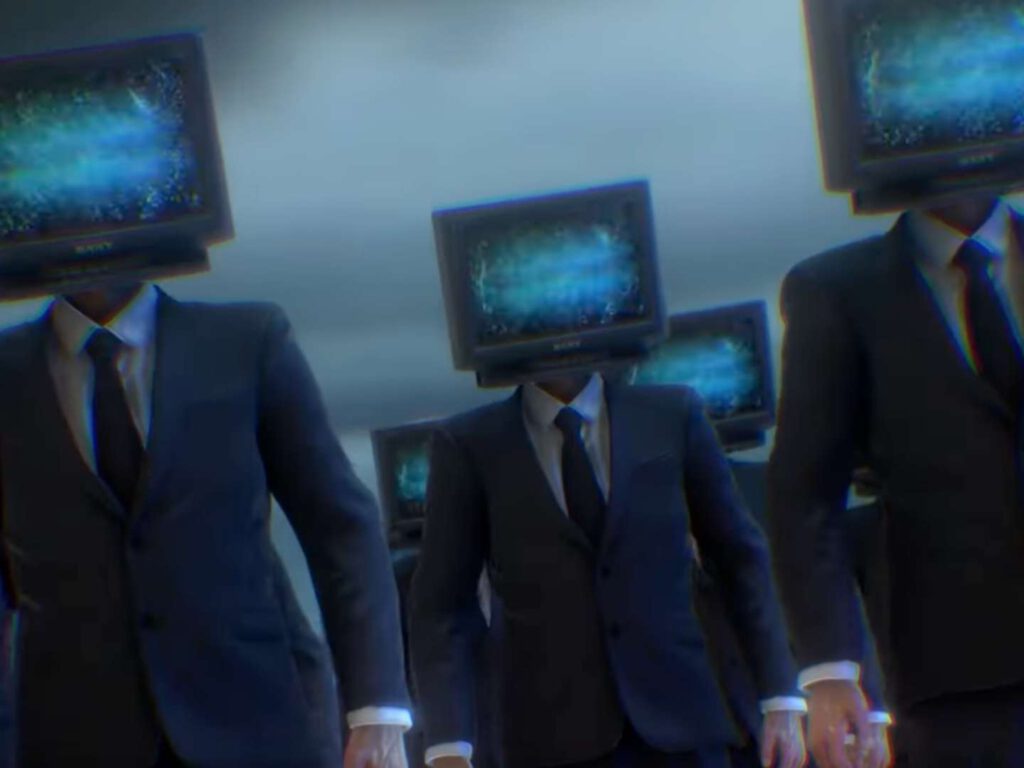

What if not the war? Everything would be different. During my meeting with people in Abkhazia, I realized how the war separated and isolated people, making them hate each other and live with prejudices and myths built about each other, which triggered even more alienation between the two societies. This alienation is a bonus for the conflict’s different involved parties so that they can play the game of „divide and rule“. And after all, because of this alienation, people like me are not likely to return home.

How current Abkhazian authorities position themselves towards the Russian war in Ukraine, Russian influence on its internal and external politics, propaganda machine and how the population reacts to what has been happening for years in Abkhazia is becoming increasingly intense.

Involvement of civil society in Abkhazia’s life is increasing, which gives hope that there can be a solid ground created by the ordinary people fighting for their fundamental rights and freedom and that this breakthrough can lead even to more considerable changes. Though, isolation in the globalized world is a heavy burden Abkhazia carries.

LELA JOBAVA graduated from Caucasus University with a degree in European Studies. She is a conflict researcher and a journalist from Gali, Abkhazia. Driven by her passion for conflict-driven reporting, storytelling, and filmmaking, Lela is committed to covering diverse ethnic, religious, linguistic, and gender-related topics, and crafting distinctive stories that highlight unique perspectives. Lela is particularly invested in providing coverage of current affairs and uncovering the untold stories of the unhurried pace of life in Abkhazia, which has remained concealed under the veil of globalization. The themes of memory and identity are integral elements in her work.