Georgia’s European integration: Where does it stand now?

„I am Georgian, and therefore I am European.“

With this brief but firm statement, Zurab Zhvania, the then Prime Minister of Georgia, commemorated his country’s accession to the Council of Europe in 1999. His sentiment resonates in Georgia through the ubiquitous presence of EU flags alongside Georgian ones on governmental buildings, as well as in public and private spaces. This symbolism signifies Georgia’s inherent belongingness to Europe, characterised by shared history, culture, values, and political thinking.

After restoring its independence in 1991, Sakartvelo, as Georgians call their country, pledged to reclaim its place within the European family. European integration has emerged as a crucial strategic objective of Georgia’s foreign policy, serving as a defining characteristic of its contemporary national identity. The Georgian society has demonstrated a strong commitment to this cause, with an impressive majority of over 80% of Georgians supporting Georgia’s EU integration. However, Georgia’s road to EU accession has been thorny and is far from complete.

A historic chance to realise its European aspirations emerged against the backdrop of the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Challenges posed by the invasion have strongly influenced the dynamics of the EU relations with its Eastern European neighbours, whose European aspirations were previously met with hesitancy, and prompted the EU to revitalise its enlargement policy. As a result, Georgia has finally received a legal European perspective. However, Georgia’s democratic backsliding and growing ties with Russia have cast doubts on the fulfilment of the long-awaited „return to Europe“ envisioned by the Georgian people. This situation raises pertinent questions about the current state of Georgia’s EU integration and its potential future trajectory.

A fuzzy breakthrough

On 28 February 2022, amidst the Battle of Kyiv, Ukraine applied for EU membership. Shortly after, on 3 March, Georgia and Moldova also submitted their applications. It is worth noting that Georgia applied somewhat reluctantly since the chairman of the ruling Georgian Dream (GD) party Irakli Kobakhidze initially argued against an immediate application.

The three states are fellow EU aspirants, belonging to the Associated Trio – a tripartite format, initiated in May 2021, which envisaged enhanced cooperation directed at coordinating efforts in pursuit of their shared goal of EU integration. Curiously, Georgia was seen as the most technically advanced in the EU integration process among the trio.

In June 2022, the EU granted EU candidate status to Ukraine and Moldova, while Georgia was left out. The Associated Trio became effectively split into different EU enlargement tracks. The main reason for Georgia’s omission, albeit not officially stated, was its democratic backsliding. Since 2019, the current Georgian government, led by the GD party, has embarked on a worrying path of ever-growing authoritarianism and illiberalism, damaging Georgia’s previously positive image of a reform-minded country undergoing a steady democratic transformation.

Despite falling short of achieving candidate status, Georgia’s European perspective was legally confirmed. This development was hard to imagine before the full-scale Russian aggression against Ukraine. Although, considering the progress achieved by Ukraine and Moldova, Georgia’s outcome seems to be a failure of the Georgian people’s European hopes. Due to its democratic backsliding, from being the most technically advanced Associated Trio country, Georgia fell to the back of the queue.

Crucially, Georgia received 12 recommendations from the European Commission (EC), addressing which promised to open the possibility of achieving EU candidate status. The recommendations include reducing political polarisation, implementing reforms to strengthen the independence of the judicial system, guaranteeing a free and pluralistic media environment, and achieving „de-oligarchisation“ among others.

Georgia’s struggle for the EU candidate status: problems on the way

The pressing question concerning Georgia’s EU integration process is whether the GD government is honest in its stated pro-European stance. Despite maintaining that it is taking all necessary measures to use the historic opportunity and attain candidate status, the government’s opaque activities reveal a different, unsettling reality. There are several important indicators that the GD government’s actions constitute a conscious sabotage of Georgia’s EU integration process.

The ruling party’s growing illiberal and authoritarian tendencies are becoming increasingly evident, undermining Georgia’s diligently built democratic foundations. An alarming example was the infamous „foreign agents“ bill, which aimed to restrict civil liberties. The bill passed its first reading on 7 March 2023, proposing that non-governmental organisations and media outlets receiving foreign funding should register as „agents of foreign influence,“ resembling the equivalent Russian law. If enacted, this law would have dealt a severe blow to Georgia’s civil society, freedom of expression, and hopes for EU accession. Following days of public outrage and large-scale protests, the bill was ultimately voted out. The outcome was celebrated as a victory for the Georgian society.

Georgia’s compliance with the EU acquis – accumulated legislation constituting the body of European law – is also decreasing. While Georgia still outperforms Ukraine and Moldova in many technical criteria, there are alarming developments in other crucial areas. One concern is the decreasing alignment of Georgia’s foreign policy with that of the EU, which has fallen from a low 44% in 2022 to only 31% in 2023. This is evident in the government’s continuous refusal to join EU sanctions imposed on Russia, Belarus, and even Myanmar.

On the contrary, amidst European states‘ significant efforts to distance themselves from Russia, Georgia’s economic ties with Russia are growing, with imports from this country increasing by 79% in 2022. The decision to resume direct flights to Russia after a nearly four-year suspension serves as yet another striking example of this. Additionally, the evidence that the GD government is helping Russia to evade Western sanctions is mounting. The Georgian government’s choice to intensify relations with Russia raises doubts about the inevitability of Georgia’s European direction.

Moreover, during the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, the GD government’s rhetoric has taken an increasingly anti-Western tone, leading to strained relations with Ukraine. The GD has parroted the Russian propaganda narrative, alleging the existence of a „global party of war“, comprising the Georgian opposition, Ukraine, and unnamed Western leaders, which is supposedly seeking to destabilise Georgia and instigate a „second front“ against Russia, thereby dragging Georgia into a war.

These developments are only more surprising when considering Russia’s military occupation of Georgian territories, namely Abkhazia and the Tskhinvali region, the latter commonly known as „South Ossetia“. Russia’s military control over the Georgian territories presents another significant political dilemma regarding Georgia’s prospects for EU accession.

At the same time, Ukraine and Moldova, two of Georgia’s Associated Trio partners, are currently ahead in their EU integration processes. While Georgia continues its democratic backsliding and escalation of the anti-Western rhetoric, Ukraine and Moldova are moving closer to the EU in a de-facto tandem, progressing in the implementation of reforms and garnering substantial rhetorical and practical backing from EU Member States.

The 12 priorities: any progress?

In June 2023, the EC released an oral report on the fulfilment of the 12 priorities, which showcased that Georgia’s progress over the year has so far been inconsistent. Only in three priorities, significant progress was achieved, namely, enhancing gender equality, nominating a new public defender, and adopting legislation directing national courts to consider European Court of Human Rights judgements.

Simultaneously, no progress was achieved on media freedom and pluralism. In recent years, Georgia saw a pronounced fall in media freedom, exemplified by the worrying increase in verbal, physical, and digital attacks on journalists and the increasingly hostile media environment to independent and opposition media. A crucially important development in this regard occurred on 22 June, when President Salome Zurabishvili pardoned Nika Gvaramia, the director general of government-critical „Mtavari“ TV company. In 2022, as the EU was going through an internal debate on Georgia’s candidate status, Gvaramia was imprisoned for alleged abuse of power after the trial which was described as „politically motivated“ by Amnesty International. The pardoning of Nika Gvaramia can pave the way for Georgian media to revert the troubling dynamics and play an important role for the EU’s assessment.

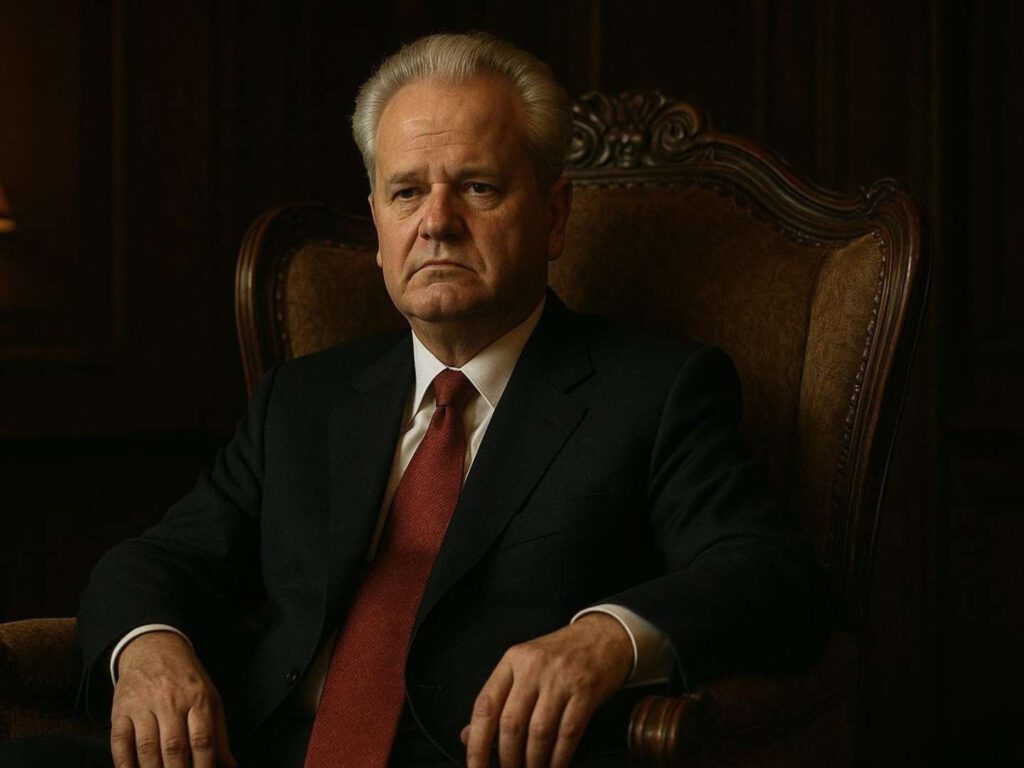

Limited progress was achieved in de-oligarchisation. The government is reluctant to make meaningful changes in this regard because the recommendation is understood to be aimed primarily at Bidzina Ivanishvili – the richest man in Georgia, an ex-Russian citizen, and a founder of the GD party. Despite no longer holding any official position in government, he still wields enormous control over Georgia’s state institutions. The GD government unyieldingly defends Ivanishvili, describing him as a philanthropist rather than an oligarch excessively influencing political and public life.

Political polarisation is another highly contentious area. Accusations against the opposition are systematic and can be described as a smear campaign. The alarming example of the government’s treatment of sentenced ex-president Mikheil Saakashvili amidst his deteriorating health conditions certainly does not help de-polarisation. On top of that, the policy choices of the current government do not increase stability in society. Human rights protection is also suffering, as the GD government insistently promotes „traditional values“, while the cases of harassment and violence against the LGBTQ+ community are rising, with perpetrators not being brought to justice effectively.

Commenting on Georgia’s progress, the government maintains it has fulfilled all the priorities. In addition, the GD leaders are resorting to blackmailing the EU with potentially disastrous consequences for the bloc in case of a negative decision on the status. The government’s stance poses a question whether the GD government is trying to shift blame for the lack of progress, or even seeking to find justifications to fully embrace the pro-Russian direction.

The potential future

The EC’s enlargement review is planned for October 2023. The Commission will assess the progress of each of the three states and issue its opinion regarding their European integration progress. Ukraine and Moldova are expecting to open membership negotiations, while for Georgia the goal is to attain the long-awaited candidate status. For the EU, any decision in this regard has the potential to bring both positive and negative consequences.

According to merit-based criteria, a chance that Georgia’s bid will be reviewed positively exists. To a certain degree, Georgia has made progress in fulfilling the 12 priorities. Yet, as things stand now, several important issues remain unaddressed, while Georgia’s alignment with the EU acquis is decreasing. To succeed in attaining candidate status, the Georgian government should genuinely implement long-standing reforms. Otherwise, granting the status to a country which does not demonstrate tangible results might undermine the EU’s conditionality.

However, the decision to grant candidate status is largely political and does not depend solely on the EC’s merit-based assessment. The geopolitical factor may prove to be crucial in the EU’s future decision on Georgia’s European integration. A positive decision can demonstrate the EU’s unbreakable commitment to the country’s European future, strengthen its position in the Caucasus region, and help to combat Russia’s involvement in Georgia by imposing obligations on the current government.

Yet, Georgia’s political woes may still prove crucial in influencing the positions of individual EU Member States, whose leaders may be wary of the prospect of welcoming „a new Hungary“ into the bloc. Thus, the current Georgian government has to honour its commitments and show its European partners that the country’s position is in line with European values. Currently, this seems unlikely, as the GD government grows only more reckless in undermining Georgian democracy.

The difficulty for the EU’s future decision lies in the possibility that any outcome can bring negative consequences. Granting candidate status in the current conditions may only strengthen the GD’s rule, as they would use such a decision to claim it is solely their achievement. In its turn, a negative decision would empower the GD to increase Euroscepticism in Georgian society.

Alternatively, Georgia’s candidate status may become a tool to give the country’s civil society and democratic opposition more power to keep their government in check and revert the current unfortunate trend in a positive direction. The EU’s determination to inflict positive change in Georgia may prove to be decisive in this regard. To achieve this, firm action against those guiding Georgia into lawlessness and authoritarianism should be taken.

However, after all, it is the Georgian people who should prove their country’s commitment to European values, the idea they have steadily championed for years. It is vitally important for Georgians to distil who should lead them forward in their European hopes. In its turn, a lot depends on the Georgian opposition’s ability to present a united platform and provide the people with concrete ideas on how to bring EU accession closer, considering that even a positive decision on candidate status for Georgia is not a panacea for the country’s political challenges.

VOLODYMYR POSVIATENKO studied European and Global Studies at the Jagiellonian University of Kraków and the University of Padova. Currently an intern at the Georgian Foundation for Strategic and International Studies – Rondeli Foundation. His research interests include the Caucasus, Eastern Europe, and the Balkans, EU enlargement, and ethnocultural and linguistic diversity.